Yesterday, I went along to the Culture and the Economy to help me answer this very perplexing question; how do you measure arts and culture. Organised by Temple Bar Cultural Trust with economists David Throsby, John O’Hagan and Finbarr Bradley, the discussion centred around value and measurement. What metrics can be used and how do you measure the intangible benefits like social cohesion, wellness, happiness, place making and identity formation that comes from artistic and cultural endeavours.

Professor David Throsby has a very valuable methodology of looking at the creative industries as part of the wider economic context. He believes we should view the creative industries as a series of concentric circles, with artists and arts organisations at the center. From here, processes of innovation that originate in the core, move out by knowledge transfer into the wider economy.

Creative workers who get their training in the core, very often move into other industries and these skills are used throughout the economy. Throsby stressed the importance of this benefit to the wider community and economy, one that is not measured or acknowledged widely enough.

Public value of arts and culture can be measured by economic value and others for cultural value. However, the predominant yard stick used to measure economic value is a cost-benefit analysis. Cultural industries create economic value via the market value from the output of their cultural goods and the demand for cultural products. While the cultural value is aesthetic, spiritual, social, historical and symbolic.

At all times we must take into account who’s value is being measured; the individual, the community, or society. Measurement of cultural value can be achieved by cultural indicators, expert appraisal and attitudinal analysis of public preferences. Throsby suggests that economists should use models developed by environmental economists in their valuing of beauty, air, materials etc. for the benefit of arts and culture. I found this rather useful in the discussion on measuring intangible cultural benefits.

Throsby also suggests a broadening of value measurements towards indicators of social well-being and happiness for example. In broadening out what we are trying to measure though it is obvious that these intangible benefits are difficult to measure and even to define.

The benefits gained by utilising new technologies for cultural organisations was discussed briefly. Throsby referred to a 2009 NESTA study with the Tate and the National Theatre, London. In both cases, audience reach was dramatically increased and more people engaged with the art forms. New audience members were brought in by engaging with both institutions via new technology.

The second part of the day saw a presentation by Professor John O’Hagan of Trinity College Dublin. John echoed much of Throsby’s points and also added an important element; the value of culture as the “social glue” of social cohesion.

My favourite presentation of the day had to go to the dynamic Finbarr Bradley. Finbarr spoke about passion and inquiry. He discussed the new paradigm of the new economy, the art of discovery and the “spirit” of the arts. Drawing from mythology, history, sociology and technology; he pointed out that the value of the arts “is in the intangible, it’s not the technology, it’s in the trust, the subtle things”. New thinking is based on spirit, meaning and experience, from the inside out and by discovering things for ourselves. Bradley encouraged us to create environments for discovery saying “the challenge for policy makers is to bring this new thinking out. To create environments where people become, to be”.

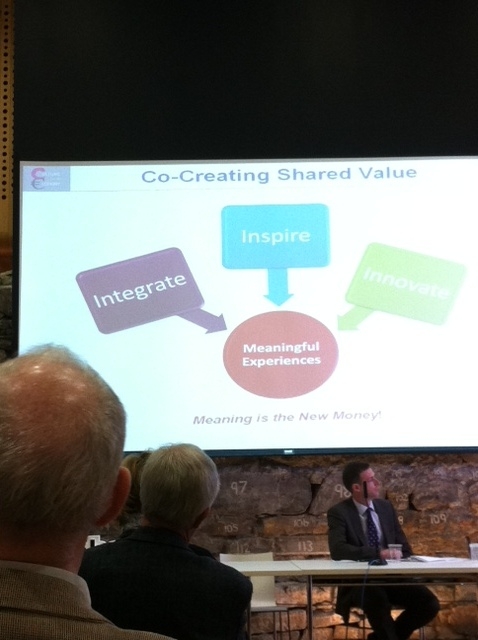

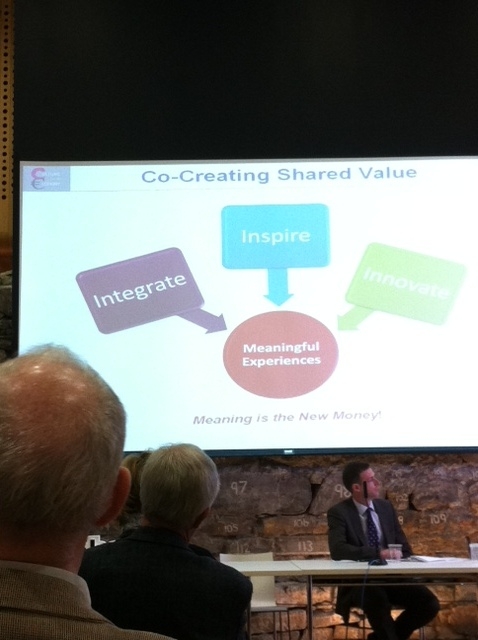

According to Bradley, the learning economy is made up of three types of knowledge, scientific, symbolic and synaptic. In the future he believes, we all must co-create shared value by inspiring, innovating and integrating our thinking, to create meaningful experiences. For Bradley “meaning equals the new money”.

As an example, Bradley described the music series Other Voices, an annual celebration of music in St. James’ Church, in Dingle, Co. Kerry. The venue is tiny only holding seventy people yet the reputation and quality of the musicians who take part each year is staggering. Such a phenomenon would not happen in Dublin, Bradley believes. There is something compelling, unique and beautiful about Dingle, the church, the atmosphere, the people and the tradition that draws musicians and audience alike to St. James’ and defines “Other Voices” as a cultural phenomenon. Other Voices then, is “meaning, rooted in place”. Pretty amazing and a wonderful way to approach the value of artistic contribution.

To conclude a wonderful morning; I took away these lessons:

– Create a powerful sense of place to find solutions, look inward as well as outward to include everyone (Bradley)

– In the modern economy the consumer and the producer constantly dance together (Bradley)

– In relation to inclusion; the arts give expression to identity, new expressions and the evolution of a new national myth (Participant from the floor)

– Create communities with different perspectives. Make value the guiding theme, then allow the community to measure their own value (Bradley)

And as to the opening question; how do we measure culture? Unfortunately there are no easy answers. As Professor Throsby says, it is a slow process but we are making steady progress. All in all, lots to think about and a very interesting morning.

Any comments and ideas coming from these discussions are very welcome. Do you have anything to add? Have you got/found a way to talk about/define the intangible value of culture? If you do, let me know and we can help shape this discussion further.

Images by the author (CC)